Continental Divide

A creative nonfiction piece I've been working on for almost two years about the contours of childhood and transition in time and space (I wrote a lot about childhood in 2023).

I

The Continental Divide slices through the middle of Rocky Mountain National Park, a diligently designated hydrogeological boundary, uncarved by rivers due to its prominence but carved into maps nonetheless. Through billions of years of geological forces, the Divide moves too slowly for humans to see. Mapmakers today translate these natural features into concentric circles on a piece of paper, unnatural marks, starting far apart and gaining in proximity, slowly first then quickly, closer and closer, before finally terminating at the peak of each mountain.

Water flows off these peaks, then toward the Gulf of Mexico or toward the Pacific, carving deserts and plains, revealing billions of years of geological history. To the east, water flows into Big Thompson River, the Cache la Poudre, the North Platte, the Platte, the Missouri, the Mississippi, the Gulf. To the west, waters quickly reach the Colorado River, which originates in the northwestern regions of the national park, then flows through the Kawuneeche Valley, through Grand Lake (and its dam), through Lake Granby (its dam), through Shadow Mountain Lake (its dam); rapids gush through steep valleys alongside United States Highway 40 and Interstate Highway 70; fast-flowing water carves arches and canyons in the sandstone desert of Utah. Then, Lake Powell. Mile-deep Grand Canyon. Lake Mead. Lake Havasu. South of Utah, the Colorado is lazy. Dams and reservoirs suck it dry for agriculture and drinking water, lowering flow to a fraction of its extent just 150 years past. The river delta is a network of canals, providing fresh water to arid communities 1500 miles from the origin, never reaching the Sea of Cortes or the Pacific.

It is in the green-blue river valley beneath the Continental Divide, at the headwaters of the Colorado River, that on August 12, 2010, five decades of cigarettes and Denver smog kill my grandmother.

II

June 18, 2006, Uncle and I cast rods into Grand Lake; brownies and rainbows and cutthroats bite drowned nightcrawlers. My six-year-old body is strong and stiff, like the trunk of a tree just growing into itself. New growth lodgepole pines dominate shorelines, their green needles thick and sharp, like fishhooks.

Nana collects worms from sandy shoreline, gives them to Uncle. She captures a small black beetle, unidentified, and holds it in shaky hands. Early summer warmth draws beetles in hordes.

Seventeen species of bark beetles in Family Dendroctonus natively populate Grand County. Bark beetles burrow through rings, dive backward in time. Egg clutches fester in woody trunks, most destined to freeze before spring.

Rising temperatures exacerbate decades-long outbreak; Dendroctonus eggs survive warm winters. Larvae crawl ring after ring through wood, kill trees from deep inside.

III

In September 1873, Isabella Bird becomes the first European woman to climb Neníisótoyóu’ú, Longs Peak, just five years following explorer and ethnologist John Wesley Powell’s ascent, the first by any European American. Bird writes letters to her sister in England about her travels, and those from her time in Colorado she publishes as A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains in 1879.

Upon reaching the tree line at 11,000 feet, Bird views both sides of the Continental Divide and as far off as Tava, the Sangre de Cristos, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas. She sees “…illimitable Plains lying idealized in the late sunlight, their baked, brown expanse transfigured into the likeness of a sunset sea rolling infinitely in waves of misty gold.”

IV

Héébe3bóoó, Flattop Mountain, two miles northwest of Neníisótoyóu’ú, reaches 12,324 feet, not quite a fourteener. Though it is uncertain if any ascent of Neníisótoyóu’ú is completed prior to the 1860s, pre-colonial Arapaho families regularly cross the Continental Divide at Héébe3bóoó; the Arapaho name literally means “Big Trail.” A difficult ascent, Bird and Powell choose Longs Peak over Flattop Mountain because of its size—the tallest, steepest, and most prominent in the park, it looms high above Héébe3bóoó. They climb and document concentric circles of topography not to travel, but to reach the summit, to conquer.

V

I live in eastern Colorado in adolescence, adrift on the “sunset sea” of “illimitable Plains,” as Bird calls them. In that time, the plains are familiar, a place I feel I know well. They are ahistorical, apoliticized. They are, simply, home. In college I research other ways of knowing and naming. Scholar and activist Dakota Wind uses the Lakota term for the region: Čhasmú. “Čhasmú,” from Lakota for “Sandhills,” for sandstone and shortgrass prairie ecosystem, which settlers and ranchers pastoralize through forced assimilation, removal, and genocide of Indigenous peoples and native plants and animals. “Čhasmú,” which settlers rename “Elbert” and “Adams” and “Washington” after founders of the state and the nation. Čhasmú, the Sandhills which cattle and sorghum raze and supplant.

VI

October 2020, fire breaks out near Granby. The East Troublesome, forest rangers call it. East Troublesome expands to over 30,000 acres in one evening, the result of decade-long drought and beetle kill that diminishes green conifers to red and brown stalks, combustible kindling. Historic buildings in Grand Lake burn down, not to mention huge parts of the forest, including a large swath of national park acreage in the Kawuneeche Valley, but most of the town survives.

I return summer 2021, masked, one year socially distanced from my childhood home. Familiar valleys, campsites, and fishing spots are charred black. Grand Lake, surrounded by beetle kill and scorch marks, in the shadow of Flattop Mountain and Longs Peak, is a tourist town that I no longer know. It had once been a place with which I was intimately familiar, but I question if it was ever truly intimacy or if it was just the illusion of childhood, the illusion of here and now, which has become there and then, suddenly inaccessible.

VII

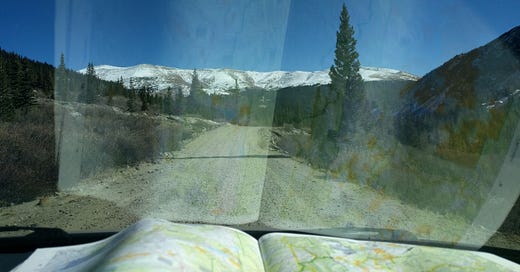

In September 2010, Mom, Dad, Uncle, and my now-widowed grandfather struggle up the Big Trail of Héébe3bóoó. The extra weight of Nana’s ashes is awkward in my backpack. I am the youngest, the fittest, they say. I am ten. They pick Flattop Mountain over Longs Peak because no one in the family has any climbing experience. Though strenuous, it is the most accessible way to reach the Continental Divide upon which Nana requests her ashes be spread.

Sad as I am to soon say goodbye to Nana, I am excited about the journey, excited to be in this place, beautiful and foreign, so unlike my hometown one hundred miles east. The excitement pushes me on, though the rest of my family requires frequent breaks.

It takes six hours to reach the timberline. Uncle and I are the only ones who think we can go on. The backbone of the continent looms hugely above us and to our north and south. The September wind is harsh where we are, whipping through pinyon bushes and sending pebbles cascading hundreds of feet down the mountain’s sheer face. The summit, where the wind is sure to be harsher, is white and blank though not yet with snow. The top is flat, though I confuse its name thinking it to be “Baldtop Mountain,” remembering Nana’s head, balding from the chemicals injected weekly to try and keep her alive just a few more days until time runs out.

VIII

Autumn 2018, I depart from Čhasmú to attend college. I study Indigenous ways of knowing and traditional ecological knowledge alongside white American perspectives of ecology, geology, and botany. I begin to socially and physically transition; I access new communities which change my perspectives radically. New knowledges complicate settler colonial narratives that were once comfortable. I learn to see how my birthplace has been in the process of changing slowly over centuries but also in the few hours of the East Troublesome Fire. This change is still in process. It is a change based on settler-colonial points of view.

The rhetoric with which my parents condemn my change of gender and body mirrors that with which scientists condemn the change of climate. The former change, however, is one of survival and foresight, while the latter is one of violence and myopia.

It is in writing that I map out concentric circles, attempt to make sense of them, to subvert the privileged memory which is central to my perspective. It is in writing that I realize that, just like a topographical map, the historical and political ramifications of which I was once unaware make the landscape, my family, my relationships to these things and to myself wholly unnatural, determined not by material relationships but by anachronistic expectations of what those relationships should look like. As a child, white and middle class, I could not yet understand the complexities of these relationships. I was simply there, taking a hike to honor my grandmother’s last wishes.

It is difficult even now to describe these concepts under the constraint of the English language and settler-colonialist American culture, which denies such understandings of environment and gender. In returning after gaining new perspectives, I relearn. I reapply my memories to these ideas which are new to me, though which have been embedded in the place for much longer than the Euro-American ideals that now purport to be true. In my own relearning, then, I start from the outside and work my way in, attempting to reach the very core, attempting to understand how concentric narratives detail my own history and memory of the place interacting with other histories and memories present there as well. It is a relearning that, like transition, will never cease.

VII

Uncle, the most outdoorsy of anyone, convinces us to keep climbing. “For Mom,” he tells his sister and father, my mother and grandfather, and they lean on their brand-new walking sticks, groaning, looking small against the massif. Neníisótoyóu’ú, two miles away, dwarfs our tiny bodies on the mountain face, dwarfs Héébe3bóoó itself. The mountains feel real, no longer mere mise-en-scène. I walk gravely up the trail; the weight of Nana in my pack feels heavier at this altitude.

We tramp through boulder fields, ever upward, the sun burning our pale faces through thin air. Eventually, a little past two—now eight hours into the ordeal—we reach the summit. North Park and Middle Park stretch out before us, and Estes Park and our home on the plains behind us. It is all so small from where we are. Everything I have ever known is constrained to a simple 360-degree view, miniature amongst the mountains and valleys, the illimitable plains.

On that bald top, that big trail, we remove the small Tupperware container that holds the last of Nana from my backpack. I think of the last time I saw her, of the rainy mountain morning we spent together in Grand Lake, far below us, before she coughed and coughed and coughed. Everything revolves around that moment.

I pour Nana’s ashes into the September wind. They cover rocks and boulders and pinyon, fly eastward, ever outward. I imagine them sedimenting a new layer on the sunbaked plains on which we live.

VI

The East Troublesome Fire has precedent. Across North America, for millennia, Indigenous peoples manage their homelands with controlled burns, keeping forests and plains from growing too densely, providing the possibility for first growth plants to reappear in the area. State and federal takeover of forest management facilitates genocidal loss of traditional ecological knowledge, slowing or stopping controlled burns.

American foresters call the first plants to regrow after a fire “early colonizers” or “pioneers,” language ripe with violence, language that considers fire and regrowth not as natural cycle, but as singular moments, progressing until combustion.

Mosses, lichens, and forbs draw small mammals who fertilize the soil. Aspens grow well in direct sunlight, enticing elk and moose. Lodgepole pines, serotinous, delay seed germination until a sudden blast of heat—fire. Fire is not a total destruction, but in fact a cyclical continuation, a repopulation of the land.

V

My return visit is greeted by little but fights with my parents. They are disappointed that I no longer attend church, that I weekly inject estrogen, that my existence does not line up exactly with how they expect it to. “Unnatural” they call me, the same way Grand Lake residents describe the East Troublesome Fire. “Unhealthy,” they say, the same thing foresters say about the pine bark beetle.

I try to ignore their anger; they try to ignore the changes. My parents minimize my newly chosen name, insisting instead on their choice: the Angel of Death, General of the Army of God. Arguments intensify, swelling as heat swells on asphalt in late summer plains. Finally, in one swift motion—“You will always be my son, but that doesn’t mean I have to love you anymore”—the disagreements become too much to ignore. I am removed from my parents’ life, but they continue, ignoring the changes, refusing to revise their mistakes.

IV

I use the term “Čhasmú” from Dakota Wind’s map titled “Makȟóčhe Wašté, Beautiful Country.” I use the mountains’ names which are posted on a University of Colorado website, tracing back these Anglicized transcriptions to a 1914 project by the Colorado Mountain Club. In conversation with Arapaho Elders Mark Soldierwolf and Lloyd Dewey, whose ancestors the State of Colorado relocate to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming in 1874, the university cannot verify the accuracy of the toponyms.

Elders and scholars and activists inspire me to research the Indigenous knowledge and toponymies of the lands which were once my home. In 2021 return, “Longs Peak” flits back and forth with “Neníisótoyóu’ú,” “Flattop” with “Héébe3bóoó.” “Čhasmú” becomes my term for Bird’s idealized, illimitable plains.

III

Climbing Longs Peak, Bird experiences not just beautiful vistas, but also fear. She is weighed down by the ridiculous dress assumed of Victorian women, by sexism in her traveling group, by the European view of the natural world that conflicts with that of her American guides, to say nothing of the Arapaho and Ute ways of knowing that long precede them. Approaching the summit, Bird writes, “from [the mountain’s] chill and solitary depths we had glimpses of golden atmosphere and rose-lit summits, not of ‘the land very far off,’ but of the land nearer now in all its grandeur, gaining in sublimity by nearness.” It is this notion of the sublime, very slightly different between the 19th century British and American English definitions, that characterizes her climb. It is a fear of the huge, god-crafted environments of the American West. It is a concept that in Europe becomes a means for men to conquer and in America for men to transcend. The sublime in Bird’s work is alive in my childhood Christian understanding of the place, in my fear of god as great as my fear of death. In both cases, the sublime embeds itself in my memory of the place’s extremity.

Isabella Bird’s ascent is difficult. Cold September wind and impenetrable boulder fields impede her journey. Regardless, upon her descent, she writes, “I would not now exchange my memories of its perfect beauty and extraordinary sublimity for any other experiences of mountaineering in any part of the world.”

II

August 11, 2014, I canoe in Grand Lake alone. Dam water sludges and mixes with trash; detrital foam floats cutthroat carcasses. Change is imminent and present. Mom and Dad ignore change, deny its existence, share with me Catholic pseudoscience denying climate change but professing a transgender epidemic. Bark beetles proliferate; beloved lodgepoles lose ruddy brown needles; fire danger climbs.

I

The Grand Canyon is named such not for its size, either culturally or geographically, but for the Grand River. This is the same origin as for Grand Junction, Grand Lake, and Grand County, Colorado. The Colorado River is called the “Grand River” until 1921, when Colorado State Representative Edward T. Taylor petitions that the Grand be renamed the Colorado along its entire length. Colorado is a Spanish term referring to the red rocks further downstream. It seems ill-fitting against the sublime greens and blues of Rocky Mountain National Park’s historic trees and lakes.

The modern red-brown beetle kill trees and the red glow of troublesome fires reflecting off midnight smoke seem applicable to this toponym, the headwaters of one of the mightiest rivers in the American West, now drained before petering out, never reaching its end in el Mar de Cortés, el Mar Bermejo. Vermilion Sea. The renaming seems predestined, although it is only through my writing that this history can summon its future.

Still, when I think of colorado, of the reddish color that now follows the river along its entire length, I think, too, of Nana, soaked in summer rain, vomiting her supper of cutthroat trout into the creek next to her fifth wheel, coughing up blood, bright red, the clot disappearing downstream.